“This is the time to be slow,

Lie low to the wall

Until the bitter weather passes.

Try, as best you can, not to let

The wire brush of doubt

Scrape from your heart

All sense of yourself

And your hesitant light.

If you remain generous,

Time will come good;

And you will find your feet

Again on fresh pastures of promise,

Where the air will be kind

And blushed with beginning.”

John O’Donohue

Many people, especially those who are quite well established in recovery, are actually pretty good in a crisis and have been able to power through the first weeks of COVID times.

Now however, as the initial shock and rapid changes begin to give way to the reality of life in lockdown, some of us might find that we are thinking and acting in ways that are confusing and unsettling. Patterns of self destructive behaviour may be tugging on our attention – either for the first time, or with an old familiar persistence.

.

Although the skills that have helped us through the panic stage will still stand us in good stead, it is perhaps time to realise that if we keep trying to run full steam ahead in firefighting mode we will eventually hit a wall and that dark hole of unhealthy behaviours may then loom large.

One alternative is to work on the longer lasting skill of emotional regulation.

The aim of the human system is to return us to a state of balance. Psychologically this can be described as the “window of tolerance”.

When we are within this window of tolerance, we are able to check in with ourselves, to notice and make sense of what we are feeling and we are able to respond wisely, rather than react and regret it later. We are not ignoring our emotions, or shoving them away, but instead we have that space where we can observe what we feel, notice it, and hear the messages that our emotions are giving us.

There are many factors that influence our ability to do this. These include our inherent genetic and biological make up, the environment in which we developed our emotional processing system, and also any events which may overwhelm it. The challenges we all face during this global pandemic and mass lockdown are perfect conditions for us to feel this last point, resulting in us feeling overwhelm.

Reacting rather than wisely responding to our emotions whilst we are outside our window of tolerance, generally happens in an automatic manner. This can feel out of our control because our survival instincts have unconsciously kicked in order to protect us from that which feels intolerable or unsafe.

These reactions often involve an urge to avoid or escape the experience, whether that action be a literal running away, using substances to numb or alter the experience, developing rituals or food behaviours to gain a sense of control, creating belief systems to make sense of what is happening, or even freezing to the extent that we realise we can’t think straight.

It is important to recognise that most people only get stuck in unhealthy emotional reactions that have worked for them in some way, at some point, in the past. They all have a benevolent intent. Yes, all of our reactions are our body’s way of keeping us protected from something that we believe deep down is intolerable to us.

Once we have a better awareness of our reactions, then we can start to think about regulating them.

.

So how can we do this?

1. Let’s firstly realise that these reactions and behaviours, however maladaptive, do have a benevolent intent. Let’s say thank you to them for keeping me safe.

2. Let’s think about which regulation skills we already have that are working. Write them down and lets consciously set out to put them into practice.

3. Let’s think about the regulation skills that we miss because they require things that are not available during lockdown. How can you reinvent these ones? If your usual way of enhancing pleasant feelings is to be in nature can you bring flowers or potted herbs into your space.

4. Let’s reduce our emotional vulnerability. Make sure we are sleeping enough, eating well, exercising enough, and looking after our physical health.

5. Identify triggers and make mindful plans to mediate these. Limiting negative news coverage is a good choice for most of us.

6. Meditation. If we are accustomed to meditation, let’s use it more. If we are not, this is a really great time to start it if it feels ok to do so.

7. Read our earlier TRC blogs for more tips on grounding and dealing with distress.

8. Let’s consciously start to name how we are feeling. Naming brings us into the real of the known and gives the opportunity to make sense of our experience.

9. Now we notice, or observe this emotion. Here we don’t judge, we just observe. By doing this, we are automatically separating ourselves from it, and this can help reduce the feeling of overwhelm. We can remain curious as we do this.

10. If the feeling is hard to grasp then let’s see if we can find it in our bodies or our thoughts. “I notice tension in my chest” “ I hear my thoughts say I can’t do this” “I feel an urge to lash out” Observe and name. Then let’s notice what shape the physical sensation is? What are the qualities of the thoughts? Fast, repetitive, loud? How strong is the urge?

11. Breathe

12. As past, maladaptive behaviours resurface, let’s see if we can pause. Instead of reaching for the chocolate, can we check in with ourselves and notice what it is that we are really craving. Is it comfort? Is it touch? Is it a need to be seen? Is it a need to hide? Do we feel sad, lonely, lost, or scared? Do we need space? Do we need to move? We might not be able to fix this, but often just making space, noticing it and naming it is enough to allow it to process through without our need to act out on it.

13. What negative beliefs about ourselves are coming up? Is it “I can’t cope”, or “I am useless”, or “I am unsafe”, or “I am not worth it”. As we connect with this, let’s ask ourselves “what would someone else looking at me right now think – would they agree with how i’m thinking towards myself?” (They probably wouldn’t)

14. As we observe all of this, what can we learn about ourselves. If we put our recovery into perspective up until now, all the work we have done already. What messages are we receiving? What do we need? Can we give that to ourselves for now?

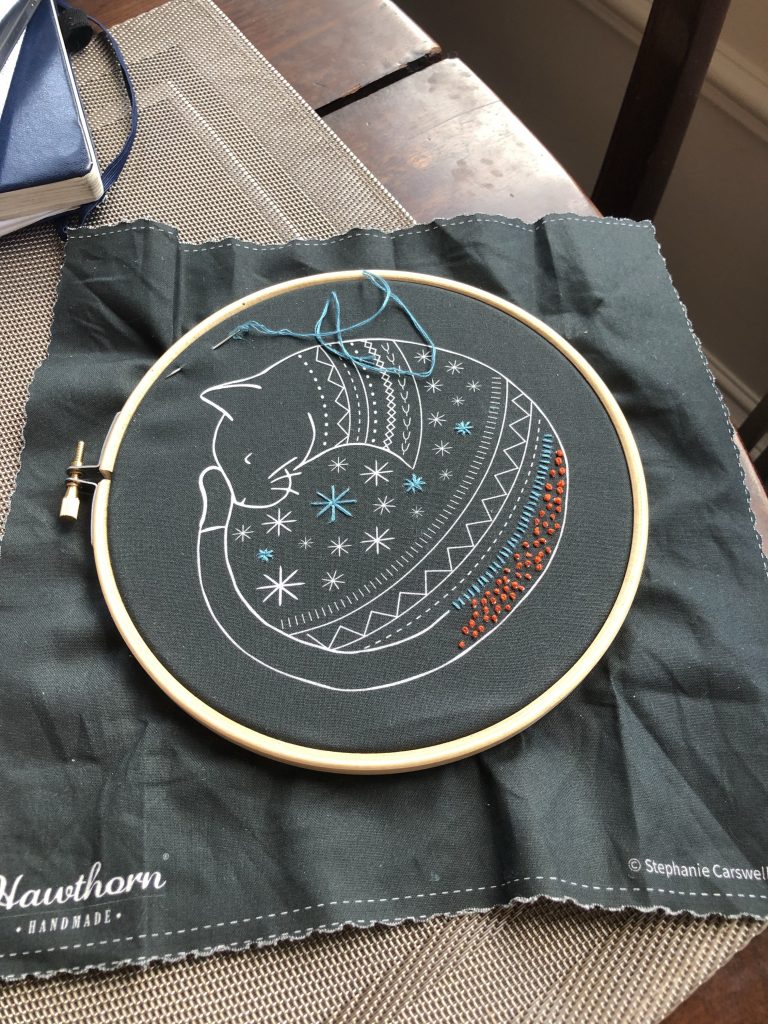

15. Find expression. Journalling, drawing, making music. For some people, writing about how they feel is tremendously cathartic and again can help the emotions process through. For others, it is through art or music. Is it time to pick up a pen and get scribbling? Get it all out on paper. Sing it out. Dance.

16. Connect to the ability of others to express similar feelings. Seek out poetry, art, songs or even memes that give form to an emotional experience.

17. Let’s think about whether we are being triggered into something unresolved from the past. This can make it feel as though it is happening in the present, all over again. Perhaps here it is time to think about whether to have some therapy to help sort through this, plus all of the above points too.

16. Stay in the present moment. See what is around you, smell the smells, see the colours, shapes. Feel your feet on the floor.

17. Drop the story or change the narrative. If we can turn our awareness away from negative thoughts this can help to break the cycle of emotions, thoughts and behaviours. Or perhaps we can reframe more accurately and find our locus of control. Are we stuck at home against our will or are we choosing to be good humans and protect each other?

17. Connect again to why you started the recovery journey. Start making plans for what you are going to do when the period of lockdown is over.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY IN FIVE CHAPTERS

I

I walk down the street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I fall in.

I am lost … I am hopeless.

It isn’t my fault.

It takes forever to find a way out.

II

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I pretend I don’t see it.

I fall in again.

I can’t believe I’m in the same place. But it isn’t my fault.

It still takes a long time to get out.

III

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I see it is there.

I still fall in … it’s a habit.

My eyes are open.

I know where I am.

It is my fault.

I get out immediately.

IV

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I walk around it.

V

I walk down another street.

Portia Nelson

Author: Michelle Scott

Michelle works at TRC which has clinics in London and Edinburgh